photo: courtesy of Tiwani Contemporary

Exhibition

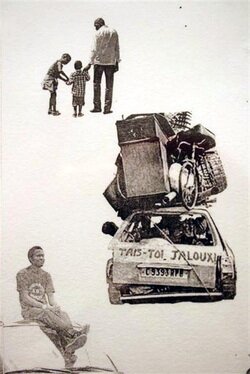

"Toussaint" | 2012 | photo: courtesy of Tiwani Contemporary

"Flags | Forget The UN" | photo: Fortune Mba Bikoro

Nathalie Mba Bikoro's career as an artist is characterised by her interdisciplinary work. Her works reflect a clear-sighted analysis of the society in which we function and are based - amongst other things - on philosophies, sociologies, histories and politics. The main principles of her art are the intensive investigations and subsequent alienation of symbols at times and their use, along with a grasp of reality by means of its limitations, later expressed in a sculptural language that aims to reveal the complexity of reality.

In "Forget the UN", Bikoro takes up the question of identity, which is materialised in African wax fabrics. The flag is advanced to a fetish of collective memory. It concretises the hopes and problems of international nations needing reconstruction. The flags represent an encounter of nations that need to re-invent and re-discover themselves. Nations like Gabon she exclaims, are searching for themselves between the illusory myth of a monolithic, the utopia of pluradist identity and a lack of knowledge about its own history: it's supposed unity is being undermined. Is this the metaphorical self-apoptosis of the nation?

The Flags|Forget the UN propose a new stage where there is no currency for territorial belonging and nations are mixed, undefined by their geographies, ethnicity, language or their colour. Made with African Wax Hollandais reminds us that it is not just a statement of bringing a re-naissance of African independence dreamed by many like Césaire but that even in their fabrications both in India and in Holland to celebrate the coming of independent African nations and the end of colonisation during the 1960’s, these colours were re-appropriated, branded, identified, symbolised, fermented as to identify a people and bringing strength, collective nationalism as well as forgetting (creating a sort of amnesia) the multi-cultural language, intermixing and dualities these were to serve generations later. It is both a gift of celebration to dreams fought by generations, it is also the continuing struggle and misappropriated inventions of how we remain to look at each other with a curious colonial or panoptic gaze, sometimes remaining in the verses of ‘we vs. them’. Here, power remains to those who can identify, land their mark and construct borders, however they all belong to one human species and to one planet.

In "Forget the UN", Bikoro takes up the question of identity, which is materialised in African wax fabrics. The flag is advanced to a fetish of collective memory. It concretises the hopes and problems of international nations needing reconstruction. The flags represent an encounter of nations that need to re-invent and re-discover themselves. Nations like Gabon she exclaims, are searching for themselves between the illusory myth of a monolithic, the utopia of pluradist identity and a lack of knowledge about its own history: it's supposed unity is being undermined. Is this the metaphorical self-apoptosis of the nation?

The Flags|Forget the UN propose a new stage where there is no currency for territorial belonging and nations are mixed, undefined by their geographies, ethnicity, language or their colour. Made with African Wax Hollandais reminds us that it is not just a statement of bringing a re-naissance of African independence dreamed by many like Césaire but that even in their fabrications both in India and in Holland to celebrate the coming of independent African nations and the end of colonisation during the 1960’s, these colours were re-appropriated, branded, identified, symbolised, fermented as to identify a people and bringing strength, collective nationalism as well as forgetting (creating a sort of amnesia) the multi-cultural language, intermixing and dualities these were to serve generations later. It is both a gift of celebration to dreams fought by generations, it is also the continuing struggle and misappropriated inventions of how we remain to look at each other with a curious colonial or panoptic gaze, sometimes remaining in the verses of ‘we vs. them’. Here, power remains to those who can identify, land their mark and construct borders, however they all belong to one human species and to one planet.

Essay review by Aarti Wa Njoroge | published in African Colours December 2012

‘My First Coup d’État’, John Dramani Mahama’s memoirs, is not the chronologically linear narrative one may expect from a historian-turned-politician looking to weave his personal lessons and achievements with the unfolding political, social and economic backdrop in Ghana.

Rather, the autobiography behaves like the circular motion of a locomotive’s wheels, driven by connecting rods and crankpins. On several occasions Mahama refers to an earlier incident or individual, but now in a different context, to state a different point. In the most unassuming of ways, one advances in time; the jigsaw puzzle fills up progressively to reveal his character and his country.

Mahama presents his story in a series of theme-based chapters. “How I got my Christian name” relates the origin and significance of traditional names, the unwillingness of mainly western teachers to understand the genealogical and other messages being passed down through them, and the influence of Christianity, co-habiting with the animism and customs it cannot fully dislodge. He remarks, as I remember doing, that modern western names are not even necessarily biblical.

In “Sankofa”, an instruction literally to “go back and get it” in Akan, and figuratively to “[derive the best of the past] in order to successfully move forward” (page 110), Mahama talks about the diaspora “[feeling] a greater [post-independence] urge to “return” to the continent to claim what has been lost or forgotten in the Middle Passage during the transatlantic slave trade – an identity, a lineage, a nationality, that rightfully belonged to them” (p110).

It is the same Middle Passage that Franco-Gabonese artist Nathalie Mba Bikoro refers to in the title of both her solo exhibition and the video of her in a Brazilan favela at Tiwani Contemporary Gallery. A personal tour that she gave on 10 November was also not linear. Her works, too, have recurring subjects and characters that re-surface – Alice with a broom, a child bride, carousel horses, animals being led for sacrifice, people painting on the ground, a search for identity. There are other similarities: her paternal grandfather, like John Dramani Mahama’s father, was one of the first to go to school.

Children in Nathalie’s village in Gabon “don’t have a hero to look up to” – they have “only what is mediatised” such as Superman. In seeking to create a “timeless, ageless character – a girl and a boy, black and white” in a state of continual time travel, she was inspired by Lewis Carroll. Nathalie’s collages, like ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’, are multi-layered. In a single frame are many – sometimes loosely connected, often enigmatic – images taken by the artist herself of selected from archives.

She starts her tour at the third collection of photo etchings. In ‘Leaving Mum II’, her sister Greta (in the role of Alice) falls into the rabbit hole, letting go of her mother, who in turn is a blindfolded goat (for Nathalie, animals often represent people) being pulled, pre-empting her biblical-style sacrifice that Greta/Alice is letting happen, willingly or otherwise. In ‘The Playground’, a sacrifice is about to happen, and so the children’s eyes are covered. Nathalie points out that the “house at the back is from [her] village”.

Her works are crammed with social commentary, such as through a topless girl wearing lipstick: the house has child prostitutes, whose clients are mostly soldiers. According to Nathalie, “the children don’t know any other life” and sacrifice their youth and health. (In ‘Chevaliers’/’Assise de Pouvoir’, Alice’s friend is becoming a child soldier. It is only a game, but his idols are behind him.)

Later, she talks about ethnic conflict over a mixed marriage. On approaching a burning village, she heard flies buzzing. People had been killed using machetes. Five years later, the village has been cleaned up and there is now a hotel. A banana plantation at the back is on the spot of the massacred ground. Nathalie relates another story of how she and her family took a young girl to be adopted in a different village, only to hear a year later that she had disappeared, probably having been kidnapped.

A few decades earlier, John Dramani Mahama’s brother Samuel Adam was adopted – in fact abducted – by a missionary couple. It took nearly thirty years to trace Samuel.

In the left-hand of the ‘Chevaliers’ diptych, crossing the equator implies crossing a passage. In the right-hand side, we see Nathalie’s mother as a human for the first time. Like a bride waiting for her dowry, she is being pulled by a man, a man pulling the boat to the shore. Nathalie was kidnapped in a pirogue, explaining that “when you are a stranger, you are a threat… People get killed and their body parts are sold to South Africa for voudou.” When one of the kidnappers recognised her uncle, a former classmate, her uncle was able to pay a huge bribe for their freedom.

It is not just people that are forcibly taken to the west or elsewhere.

Catholic priests wanted Africans to get rid of their masks, which were no longer being used ritually – according to Nathalie, they were even used to open cans of food. Yet one priest, who clearly saw their value, sold masks from Nathalie’s family to a French collector. When they appeared in an exhibition with identifying details (age, village), Nathalie’s uncle called her, exclaiming, “They’ve stolen our jewels!” (See Give It Back: Art Objects Belong Where They’re Found, Le Monde diplomatique, September 2012, for a more exhaustive story on the topic: “About 5,000 pieces found in 1911 in Machu Picchu by the archaeologist and Yale professor Hiram Bingham, and formally loaned by Peru 100 years ago for 12 months so that they could be restored, are still in the Peabody Museum of New Haven. Peru has been asking for them back since 1920, but Yale won’t allow Peruvian archaeologists access to them. Last year an agreement was reached: Peru must build a museum dedicated to the Inca site in Cuzco and leave the finest pieces on permanent loan to the Peabody.”)

During the tour, Nathalie points to a possible reference to Sarah Baartman. Sarah Baartman’s remains were returned to South Africa in 2002 after five years’ negotiations.

In ‘Family Tree’ Alice, knowing her future (domestic chores, the relationships she will have with men) will be decided for her, is pointing her broomstick, as if she is shooting at the two cranial representations above her: Fang masks from that side of her heritage co-exist with the beheaded trophy deer from her French hunter-grandfather. Not as blatant as David Chancellor’s ‘Hunter’ portraits recently exhibited at the Jack Bell Gallery (which were even more chilling for being recent), these could still, for some, romanticise what is effectively poaching.

Where there is a decapitation of a whale carcass, Nathalie states the bones are sold to Koreans.

When we are in front of ‘Chevaliers’/’Assise de Pouvoir’, she talks about a man who brought over a termite house to a 2010 design and art fair in Paris and called it ‘Seat of Power’. He destroyed the landscape as he was seeking the ‘perfect’ termite hill, but the soldiers did not care – they were getting paid. Everyone was oblivious of the political structure of the termites.

Violence and destruction are never far away. Nathalie’s family is in the foreground of ‘The Trial’. Hanging “bananas” in the silhouette are in fact hanging people. “Alice is being judged,” Nathalie tells us. She zooms in on the suspended buckets of water, which represent a torture device. If this were not bad enough, the water falling into the playground turns to blood, soiling it, and with it, Alice’s innocence. In ‘Bananas’, Nathalie asks if “[she is] picking stones to break the cord [of the hanging people] above her”.

When showing ‘[B]rushing [B]orders’, Nathalie says the “exact same sacrifices” happened in ancient Greece, yet we do not admit it.

According to Nathalie, miners in South Africa are poor, malnourished people from India, China, even Japan – something else we do not speak about. ’34 Fell from the Sky’ is in memory of the Lonmin miners, each one represented by a bottle, who died. Working seven days a week and afraid, they were forced to protest. One was decapitated and made into a scarecrow. “What kind of freedom-fighting is this?” Nathalie asks. A drunk has lost his mind. In ‘The Gates/A Little Night Music’, a homeless professor wearing found clothes has lost his mind because his students went to work in the government and politics, breaking his heart. In ‘My First Coup d’État’, John Dramani Mahama sees his father’s favourite driver, Mallam, go – in his words – mad, apparently as a result of taking ‘wee’ [sic]. Both Nathalie Mba Bikoro and John Dramani Mahama show poignancy in mental breakdown.

The right of ‘The Orchestra/La bataille de Mimbeng’ refers to north Gabon’s German past; First World War tanks have been abandoned in the forest. On the left is everyday life, the inevitable noise of the traffic. In the middle, Alice is about to jump from the house. Leaders are meeting to try to resolve a local conflict, but they are useless – there is no such thing as justice. She is sick of it. (Think of “Off with their heads” in ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’.)

In her video ‘Le Passage Devés’, shot in St Louis in Senegal, she covers her face with thin gold leaves, to become anonymous. She removes nails from one goat’s heart with her mouth and puts them on another goat’s heart, also suspended on a piece of string. She keeps running between the two. She could not have filmed this in Gabon; she would have been considered a shaman.

Defiance, challenging the status quo, are recurring subjects in her art, and in her mind. Nathalie interprets Eve bringing Adam the apple as a way of asking Adam who he is. Eve’s decision to rebel against his father “breaks the system”. In ‘Cutting down the Fetish Tree’, slave ships are being pushed out. Yet, for Nathalie, “The master/slave relationship slows us down as a society. We can get away from the dichotomy. The more we repeat it, the more we will [be in a deadlock]. Josephine Baker played up the stereotype.” Rather, it is about the “crystal moment” – getting away from the discourse of the black and white dichotomies, like putting a light through a crystal and seeing all the colours. The title of one of Nathalie’s works is telling: black or white, tears are salty.

Nathalie tells another story of she caused a Nigerian women to lose her identity by telling her that wax hollandais was only used after the 1950s. Dutch wax is part of the ‘arc of mutual inspiration’ in west Africa, like the highlife and hiplife that Dr Halifu Osumare writes about in ‘The Hiplife in Ghana: West African Indigenization of Hip-Hop’.

Nathalie’s aunts are performing a dancing ritual, but “we don’t know what they are celebrating”. (In the left-hand of the ’Assise de Pouvoir’ diptych a family is also dancing.) There are two-tiered buckets for Chinese water torture reminiscent of that administered by the Stasi, the East German secret police. Below the buckets is a priest photographing a goat with his iPad, oblivious to the dripping water.

In ‘Les statues meurent aussi/We are Martians’ the scene is dilapidated. It not a pilgrimage site. Alice, alone, meets an astronaut. The 1969 moon landing is a collective dream – “what are we going to do with our future? Wait a minute! This is not a different planet. She releases a white balloon as a flag of peace.” In the last five years, Americans have been investing in Gabon, but they do not know what they are coming into. They bring their dreams, their ideas on what they can improve, but with no idea of what is on the ground. They will make mistakes: the dialogue is not working.

Opposite ‘Les statues meurent aussi/We are Martians’, with its American flag, are the flags of ‘Forget the UN’. Another dialogue that is not working?

Toussaint L’Ouverture’s rocking horse in ‘Family Tree’ does not advance, symbolising Nathalie dealing with her emotions, discovering her identity, while not always moving forward. It could also be the frustration of being stuck in one place (and time) until whatever you are attempting to understand clicks. In ‘The Carousel/Blancs ou noirs, toutes les larmes sont salées’, real animals are suspended like toys. The Toussaint horse re-appears. Alice is trying to find herself.

Nathalie’s most recent work, filmed at the Tiwani Contemporary Gallery on the night of the opening, offer another solution. With meat tied to her feet, she stands on hot plates for over twenty minutes. The burning meat and skin are like slash-and-burn agriculture. We can start again.

Rather, the autobiography behaves like the circular motion of a locomotive’s wheels, driven by connecting rods and crankpins. On several occasions Mahama refers to an earlier incident or individual, but now in a different context, to state a different point. In the most unassuming of ways, one advances in time; the jigsaw puzzle fills up progressively to reveal his character and his country.

Mahama presents his story in a series of theme-based chapters. “How I got my Christian name” relates the origin and significance of traditional names, the unwillingness of mainly western teachers to understand the genealogical and other messages being passed down through them, and the influence of Christianity, co-habiting with the animism and customs it cannot fully dislodge. He remarks, as I remember doing, that modern western names are not even necessarily biblical.

In “Sankofa”, an instruction literally to “go back and get it” in Akan, and figuratively to “[derive the best of the past] in order to successfully move forward” (page 110), Mahama talks about the diaspora “[feeling] a greater [post-independence] urge to “return” to the continent to claim what has been lost or forgotten in the Middle Passage during the transatlantic slave trade – an identity, a lineage, a nationality, that rightfully belonged to them” (p110).

It is the same Middle Passage that Franco-Gabonese artist Nathalie Mba Bikoro refers to in the title of both her solo exhibition and the video of her in a Brazilan favela at Tiwani Contemporary Gallery. A personal tour that she gave on 10 November was also not linear. Her works, too, have recurring subjects and characters that re-surface – Alice with a broom, a child bride, carousel horses, animals being led for sacrifice, people painting on the ground, a search for identity. There are other similarities: her paternal grandfather, like John Dramani Mahama’s father, was one of the first to go to school.

Children in Nathalie’s village in Gabon “don’t have a hero to look up to” – they have “only what is mediatised” such as Superman. In seeking to create a “timeless, ageless character – a girl and a boy, black and white” in a state of continual time travel, she was inspired by Lewis Carroll. Nathalie’s collages, like ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’, are multi-layered. In a single frame are many – sometimes loosely connected, often enigmatic – images taken by the artist herself of selected from archives.

She starts her tour at the third collection of photo etchings. In ‘Leaving Mum II’, her sister Greta (in the role of Alice) falls into the rabbit hole, letting go of her mother, who in turn is a blindfolded goat (for Nathalie, animals often represent people) being pulled, pre-empting her biblical-style sacrifice that Greta/Alice is letting happen, willingly or otherwise. In ‘The Playground’, a sacrifice is about to happen, and so the children’s eyes are covered. Nathalie points out that the “house at the back is from [her] village”.

Her works are crammed with social commentary, such as through a topless girl wearing lipstick: the house has child prostitutes, whose clients are mostly soldiers. According to Nathalie, “the children don’t know any other life” and sacrifice their youth and health. (In ‘Chevaliers’/’Assise de Pouvoir’, Alice’s friend is becoming a child soldier. It is only a game, but his idols are behind him.)

Later, she talks about ethnic conflict over a mixed marriage. On approaching a burning village, she heard flies buzzing. People had been killed using machetes. Five years later, the village has been cleaned up and there is now a hotel. A banana plantation at the back is on the spot of the massacred ground. Nathalie relates another story of how she and her family took a young girl to be adopted in a different village, only to hear a year later that she had disappeared, probably having been kidnapped.

A few decades earlier, John Dramani Mahama’s brother Samuel Adam was adopted – in fact abducted – by a missionary couple. It took nearly thirty years to trace Samuel.

In the left-hand of the ‘Chevaliers’ diptych, crossing the equator implies crossing a passage. In the right-hand side, we see Nathalie’s mother as a human for the first time. Like a bride waiting for her dowry, she is being pulled by a man, a man pulling the boat to the shore. Nathalie was kidnapped in a pirogue, explaining that “when you are a stranger, you are a threat… People get killed and their body parts are sold to South Africa for voudou.” When one of the kidnappers recognised her uncle, a former classmate, her uncle was able to pay a huge bribe for their freedom.

It is not just people that are forcibly taken to the west or elsewhere.

Catholic priests wanted Africans to get rid of their masks, which were no longer being used ritually – according to Nathalie, they were even used to open cans of food. Yet one priest, who clearly saw their value, sold masks from Nathalie’s family to a French collector. When they appeared in an exhibition with identifying details (age, village), Nathalie’s uncle called her, exclaiming, “They’ve stolen our jewels!” (See Give It Back: Art Objects Belong Where They’re Found, Le Monde diplomatique, September 2012, for a more exhaustive story on the topic: “About 5,000 pieces found in 1911 in Machu Picchu by the archaeologist and Yale professor Hiram Bingham, and formally loaned by Peru 100 years ago for 12 months so that they could be restored, are still in the Peabody Museum of New Haven. Peru has been asking for them back since 1920, but Yale won’t allow Peruvian archaeologists access to them. Last year an agreement was reached: Peru must build a museum dedicated to the Inca site in Cuzco and leave the finest pieces on permanent loan to the Peabody.”)

During the tour, Nathalie points to a possible reference to Sarah Baartman. Sarah Baartman’s remains were returned to South Africa in 2002 after five years’ negotiations.

In ‘Family Tree’ Alice, knowing her future (domestic chores, the relationships she will have with men) will be decided for her, is pointing her broomstick, as if she is shooting at the two cranial representations above her: Fang masks from that side of her heritage co-exist with the beheaded trophy deer from her French hunter-grandfather. Not as blatant as David Chancellor’s ‘Hunter’ portraits recently exhibited at the Jack Bell Gallery (which were even more chilling for being recent), these could still, for some, romanticise what is effectively poaching.

Where there is a decapitation of a whale carcass, Nathalie states the bones are sold to Koreans.

When we are in front of ‘Chevaliers’/’Assise de Pouvoir’, she talks about a man who brought over a termite house to a 2010 design and art fair in Paris and called it ‘Seat of Power’. He destroyed the landscape as he was seeking the ‘perfect’ termite hill, but the soldiers did not care – they were getting paid. Everyone was oblivious of the political structure of the termites.

Violence and destruction are never far away. Nathalie’s family is in the foreground of ‘The Trial’. Hanging “bananas” in the silhouette are in fact hanging people. “Alice is being judged,” Nathalie tells us. She zooms in on the suspended buckets of water, which represent a torture device. If this were not bad enough, the water falling into the playground turns to blood, soiling it, and with it, Alice’s innocence. In ‘Bananas’, Nathalie asks if “[she is] picking stones to break the cord [of the hanging people] above her”.

When showing ‘[B]rushing [B]orders’, Nathalie says the “exact same sacrifices” happened in ancient Greece, yet we do not admit it.

According to Nathalie, miners in South Africa are poor, malnourished people from India, China, even Japan – something else we do not speak about. ’34 Fell from the Sky’ is in memory of the Lonmin miners, each one represented by a bottle, who died. Working seven days a week and afraid, they were forced to protest. One was decapitated and made into a scarecrow. “What kind of freedom-fighting is this?” Nathalie asks. A drunk has lost his mind. In ‘The Gates/A Little Night Music’, a homeless professor wearing found clothes has lost his mind because his students went to work in the government and politics, breaking his heart. In ‘My First Coup d’État’, John Dramani Mahama sees his father’s favourite driver, Mallam, go – in his words – mad, apparently as a result of taking ‘wee’ [sic]. Both Nathalie Mba Bikoro and John Dramani Mahama show poignancy in mental breakdown.

The right of ‘The Orchestra/La bataille de Mimbeng’ refers to north Gabon’s German past; First World War tanks have been abandoned in the forest. On the left is everyday life, the inevitable noise of the traffic. In the middle, Alice is about to jump from the house. Leaders are meeting to try to resolve a local conflict, but they are useless – there is no such thing as justice. She is sick of it. (Think of “Off with their heads” in ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’.)

In her video ‘Le Passage Devés’, shot in St Louis in Senegal, she covers her face with thin gold leaves, to become anonymous. She removes nails from one goat’s heart with her mouth and puts them on another goat’s heart, also suspended on a piece of string. She keeps running between the two. She could not have filmed this in Gabon; she would have been considered a shaman.

Defiance, challenging the status quo, are recurring subjects in her art, and in her mind. Nathalie interprets Eve bringing Adam the apple as a way of asking Adam who he is. Eve’s decision to rebel against his father “breaks the system”. In ‘Cutting down the Fetish Tree’, slave ships are being pushed out. Yet, for Nathalie, “The master/slave relationship slows us down as a society. We can get away from the dichotomy. The more we repeat it, the more we will [be in a deadlock]. Josephine Baker played up the stereotype.” Rather, it is about the “crystal moment” – getting away from the discourse of the black and white dichotomies, like putting a light through a crystal and seeing all the colours. The title of one of Nathalie’s works is telling: black or white, tears are salty.

Nathalie tells another story of she caused a Nigerian women to lose her identity by telling her that wax hollandais was only used after the 1950s. Dutch wax is part of the ‘arc of mutual inspiration’ in west Africa, like the highlife and hiplife that Dr Halifu Osumare writes about in ‘The Hiplife in Ghana: West African Indigenization of Hip-Hop’.

Nathalie’s aunts are performing a dancing ritual, but “we don’t know what they are celebrating”. (In the left-hand of the ’Assise de Pouvoir’ diptych a family is also dancing.) There are two-tiered buckets for Chinese water torture reminiscent of that administered by the Stasi, the East German secret police. Below the buckets is a priest photographing a goat with his iPad, oblivious to the dripping water.

In ‘Les statues meurent aussi/We are Martians’ the scene is dilapidated. It not a pilgrimage site. Alice, alone, meets an astronaut. The 1969 moon landing is a collective dream – “what are we going to do with our future? Wait a minute! This is not a different planet. She releases a white balloon as a flag of peace.” In the last five years, Americans have been investing in Gabon, but they do not know what they are coming into. They bring their dreams, their ideas on what they can improve, but with no idea of what is on the ground. They will make mistakes: the dialogue is not working.

Opposite ‘Les statues meurent aussi/We are Martians’, with its American flag, are the flags of ‘Forget the UN’. Another dialogue that is not working?

Toussaint L’Ouverture’s rocking horse in ‘Family Tree’ does not advance, symbolising Nathalie dealing with her emotions, discovering her identity, while not always moving forward. It could also be the frustration of being stuck in one place (and time) until whatever you are attempting to understand clicks. In ‘The Carousel/Blancs ou noirs, toutes les larmes sont salées’, real animals are suspended like toys. The Toussaint horse re-appears. Alice is trying to find herself.

Nathalie’s most recent work, filmed at the Tiwani Contemporary Gallery on the night of the opening, offer another solution. With meat tied to her feet, she stands on hot plates for over twenty minutes. The burning meat and skin are like slash-and-burn agriculture. We can start again.

Africa Summer Festival | curated by Yinka Shonibare MBE | African Centre Covent Garden